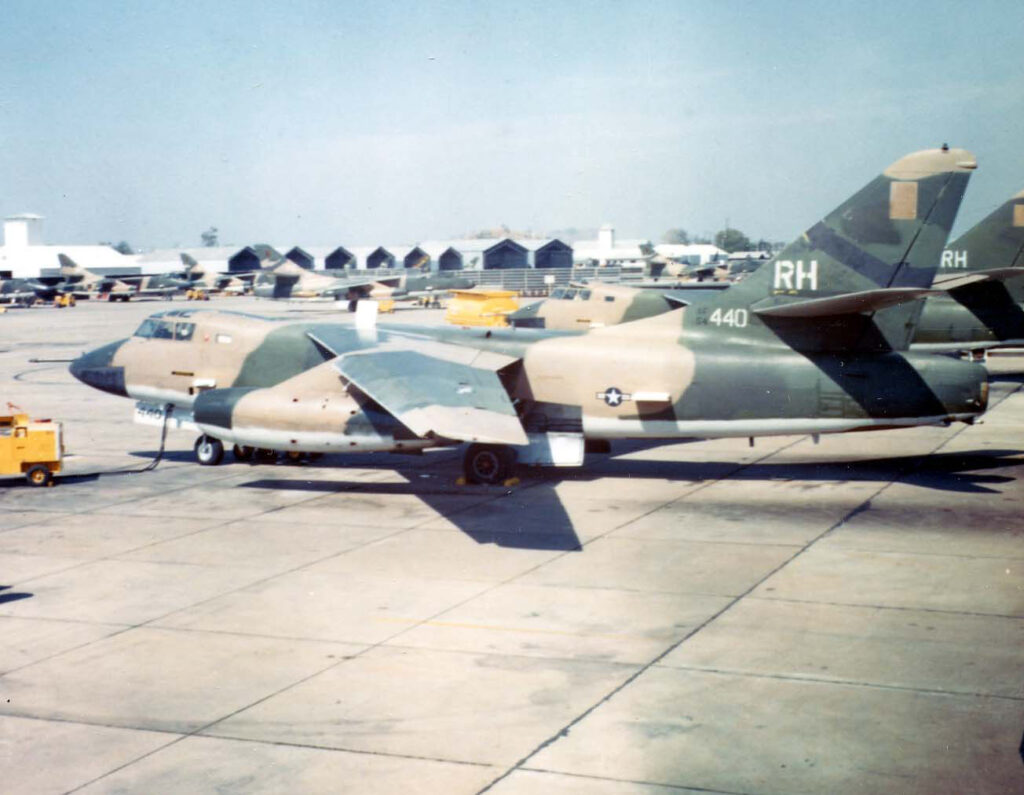

Unarmed Douglas EB-66 electronic warfare aircraft detected and jammed enemy air defense radars. Though small in number, EB-66s and their crews remained in high demand as part of the total strike package in bombing missions against North Vietnam.

The North Vietnamese used radar signals to detect incoming aircraft, guide their MiG fighters, and aim surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and antiaircraft guns. U.S. Air Force EB-66s conducted “electronic warfare” against these radars to render them useless.

The first USAF electronic warfare B-66s went to Southeast Asia in the spring of 1965. EB-66 crews detected and gathered information about enemy radar locations and frequencies. They also used jamming equipment to interrupt enemy radar signals.

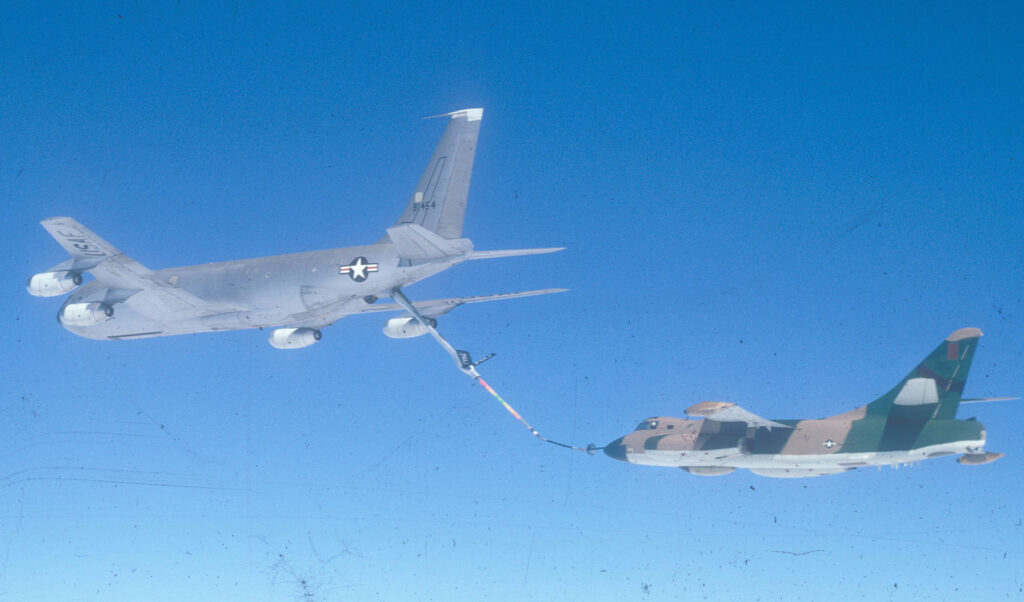

USAF bombing missions deep into North Vietnam always required EB-66 support, even though there were relatively few EB-66s. Moreover, the B-66 was out of production, so repair and shortages of spare parts made it difficult to keep aircraft flying.

Losses further reduced the number of available aircraft. EB-66s were so successful that the enemy specifically targeted them. MiG fighters shot down one EB-66 and SAMs shot down five. Eleven more EB-66s were lost to accidents.

Despite these problems, EB-66 crews continued flying and providing essential support to strike aircraft to the end of the war in 1973.

Rescue of Bat 21

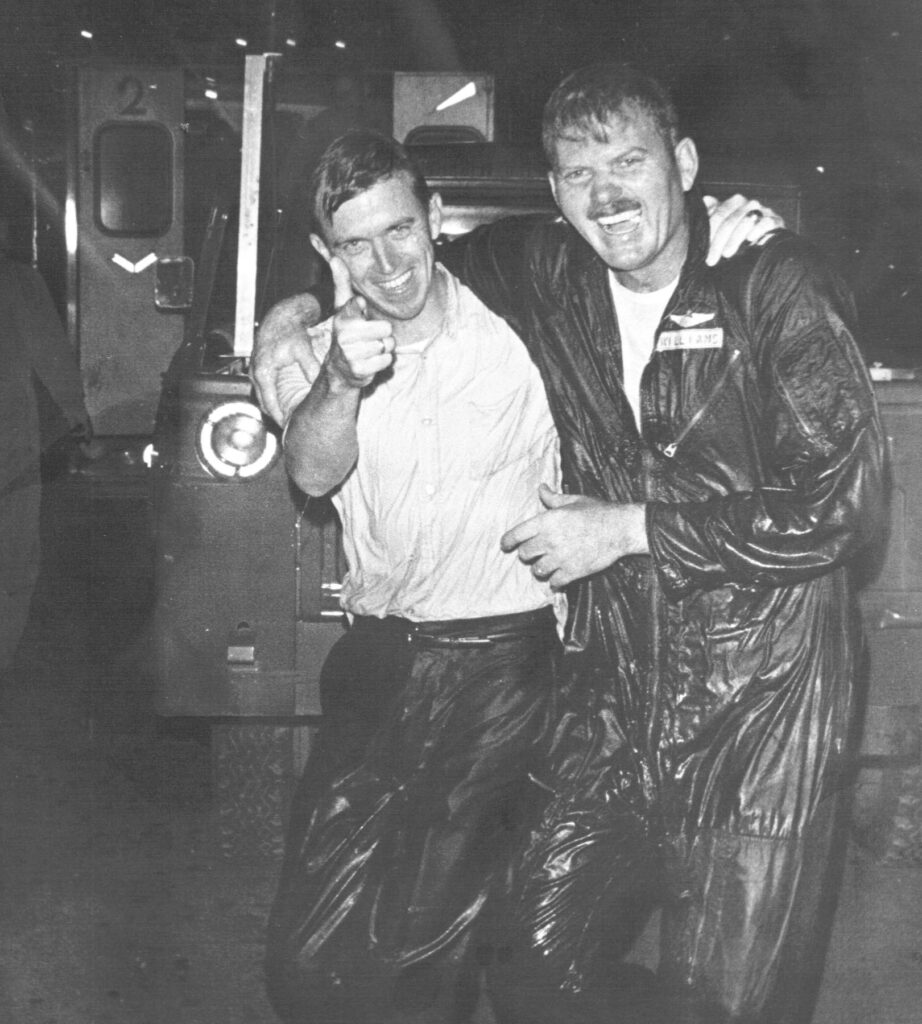

In one of the most difficult rescues of the war, Lt. Col. Iceal “Gene” Hambleton was recovered from enemy territory after 11 1/2 days on the ground. This was the largest rescue operation in USAF history.

On April 2, 1972, 53-year-old navigator Lt. Col. Hambleton was the only crewmember to safely eject after his EB-66 (call sign Bat 21) was hit by a surface-to-air missile. He landed in the middle of the spearhead of the enemy’s massive Easter Offensive.

Several courageous attempts were made to recover Hambleton. After the loss of numerous aircraft and personnel, a new plan was devised. Authorities planned a ground recovery, but they needed Hambleton to move away from his hiding spot to a nearby river.

Knowing Hambleton was an avid golfer, authorities gave him directional and distance information by naming specific holes at different golf courses. One forward air controller, Capt. Harold Icke, spent countless hours orbiting near Hambleton and communicating by radio throughout the ordeal.

After “playing” nine holes and nearing collapse from hunger and exhaustion, Hambleton had moved to a location where U.S. Navy SEAL LT Tom Norris and South Vietnamese SEAL Petty Officer Nguyen Van Kiet safely recovered him.

B-66 Destroyer photos

B-66 Destroyer related patches