In March of 1965 an aerial interdiction campaign against ground targets in North Vietnam – Operation Rolling Thunder – got underway. In response, the North Vietnamese began strengthening their air defenses, but not without help. In May 1965, reconnaissance flights over North Vietnam revealed the first surface-to-air (SAM) sites, with Soviet-built S-75 Dvina missiles, more commonly known by the NATO codename SA-2 Guideline and their accompanying Fan Song detection and targeting radar.

U.S. military strategists quickly took notice when on July 24, 1965, the new technology shot down a USAF F-4C Phantom II. It was the beginning of a chilling twist in air warfare; even the very next day, an SA-2 brought down an American reconnaissance drone flying at 59,000 feet. The game had irrevocably changed.

What should have been no surprise served as a wake-up call for the U.S., albeit in a reactionary construct. Retaliatory strikes were directed at offending SAM sites, but were met with failure as the North Vietnamese often substituted fake missiles and used dummy sites as a ploy. The losses continued to mount as more aircraft were lost either directly or indirectly due to the SA-2s; as the threat of the radar-guided missiles forced strikers down to low altitudes—out of the deadly missile’s performance envelope, but within the effective range of the dense anti-aircraft artillery (AAA, or Triple-A). The missile sites proved exceptionally successful at airspace denial, and drastic measures were needed to counter the deadly threat they presented.

In October 1965, a group of ten specially-selected United States Air Force aviators were gathered at a remote part of Eglin Air Force Base in the Florida panhandle. This highly-classified operation, called Project Weasel, was designed to develop new equipment and tactics to counter the SAM threat over Vietnam.

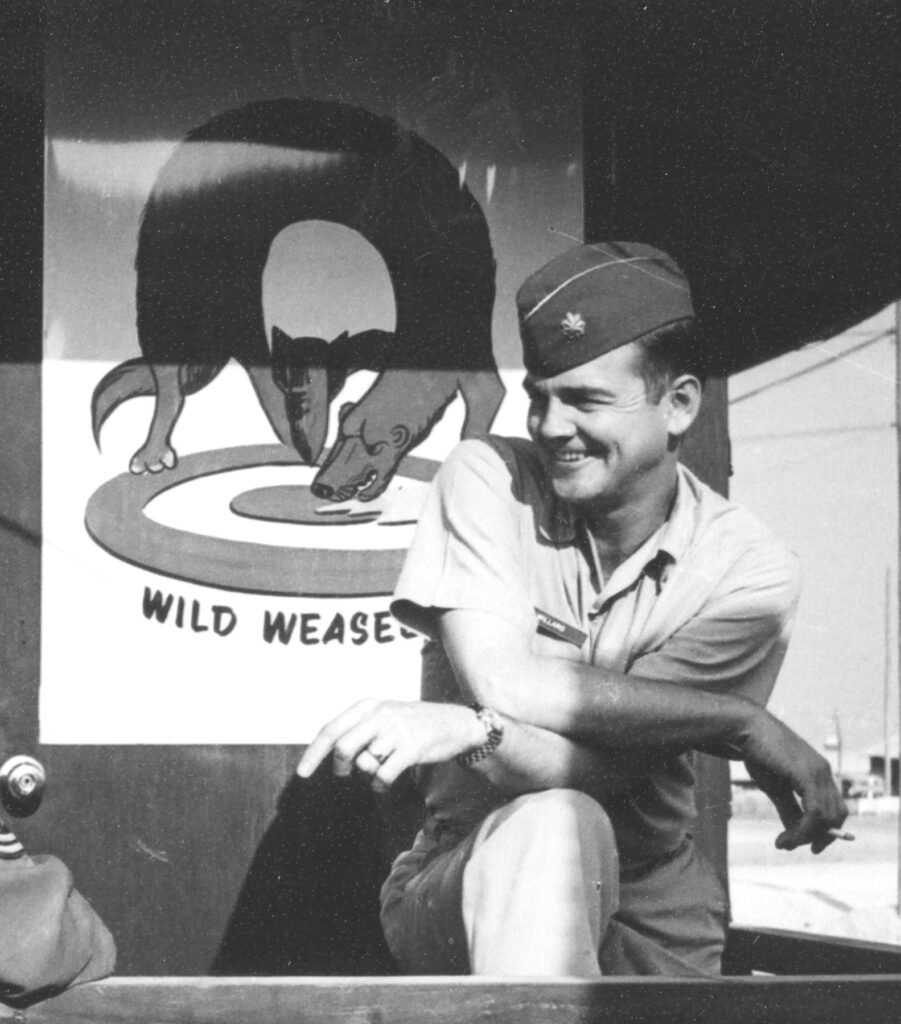

“It was really hush-hush,” describes retired USAF Lieutenant Colonel Allen Lamb, “and they were really depending on us.”

Installed in their North American F-100F Super Sabre aircraft were radar homing and warning receivers such as the APR-35, taken from the CIA’s Lockheed U-2 spyplane and designed to locate the signal emitted by the SAM radar operators. The aircraft also featured SAM launch detectors, which would notify the crew if a missile had been launched.

Under the direction of Major Gary Willard, the men hurriedly trained for the new mission—currently known as Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses, or SEAD (pronounced “seed”). Within a month, the group and their aircraft deployed in complete secrecy to Korat Royal Thai Air Base, arriving in theater Thanksgiving Day of 1965. The deadly cat-and-mouse game between the “Wild Weasels” and the North Vietnamese air defenses had started, beginning with flights near the border region of Vietnam and Laos to gather electronic intelligence and build situational awareness (SA) of the NVA air defenses.

Wild Weasel and the F-100F

The Air Force placed great hope on the success of the Wild Weasel concept. Project Wild Weasel used modified two-seat F-100Fs, with the pilot flying and firing weapons from the front seat, while an electronic warfare officer (EWO) tracked enemy radar systems in the back seat. These trailblazers created, tested and proved SAM suppression tactics in combat.

In November 1965 the first Wild Weasel crews deployed to Southeast Asia — only four months after the first USAF SA-2 loss in Southeast Asia. Their four F-100Fs had been hastily modified under great secrecy with equipment that detected enemy radar sites. Reflecting the urgent need, these volunteers planned to finish their training in combat over North Vietnam, and they flew their first anti-SAM mission on Dec. 1. This first group was replaced in February 1966 by a second group that received three more modified F-100Fs.

Typically, one F-100F Wild Weasel crew hunted enemy SAM radars with electronic equipment. After pinpointing them visually, they attacked the radars with rockets. Accompanying F-105s then followed with bombs or rockets.

The pioneer Wild Weasels proved the concept and developed effective tactics, destroying nine SA-2 sites and suppressing enemy SAMs for strike forces. Even so, three of the seven F-100Fs were lost (two in combat). The more powerful F-105F Wild Weasel III replaced Wild Weasel I F-100Fs in the summer of 1966 (there was no production Wild Weasel