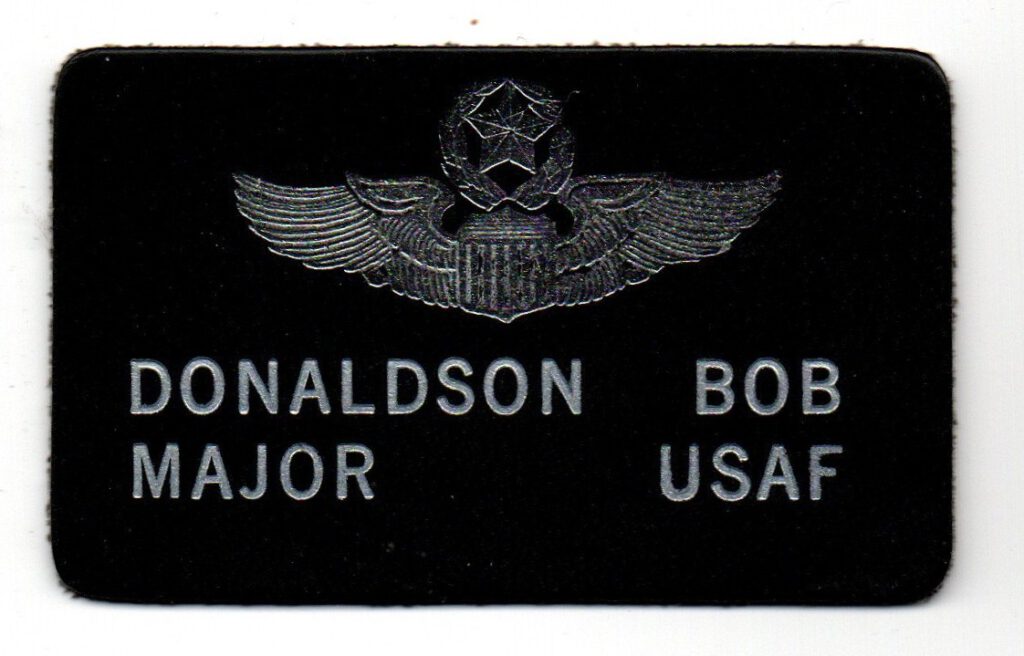

written by Warren Thompson and contributions from Maj Bob Donaldson 509th FIS and his son Maj. Rob Donaldson.

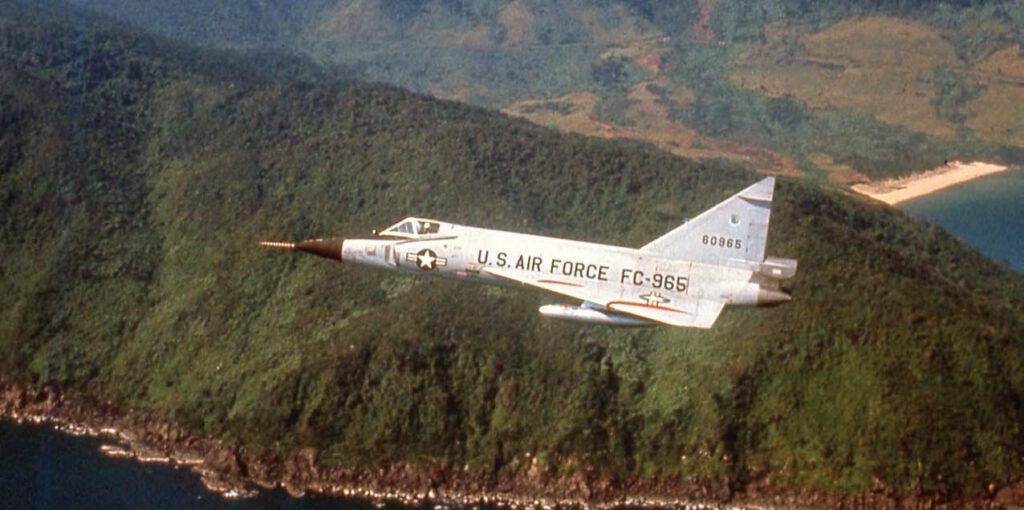

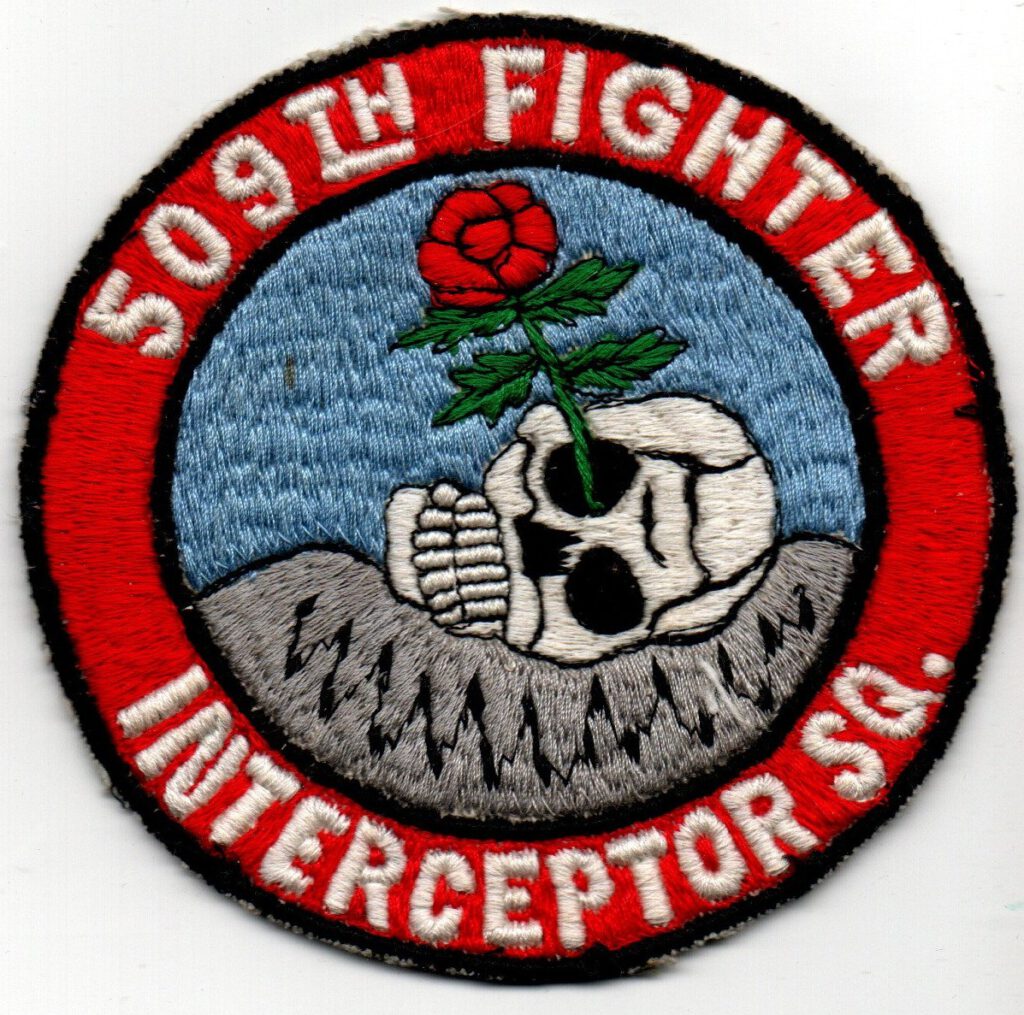

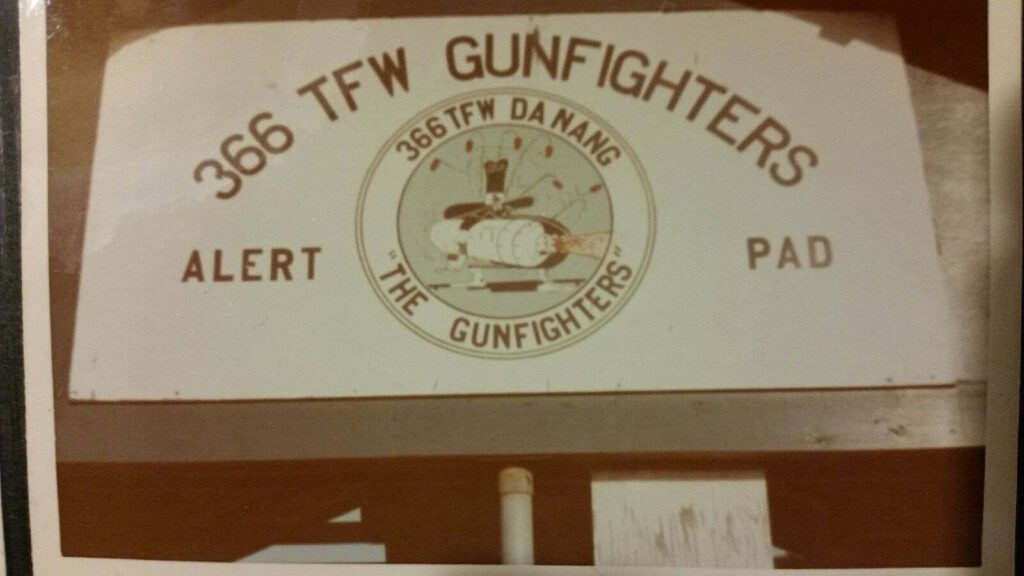

The Convair F-102 Delta Dagger was one of the first USAF combat aircraft to be deployed to Vietnam, yet its impressive war record is often overlooked. Combat Aircraft charts the type’s service in South-east Asia, including the use of airto- air missiles in the ground attack role! The F-102 squadrons [the 64th and 509th Fighter Interceptor Squadrons, FIS] based at Clark Air Base quietly and effectively carried out a unique combat mission that was vital to the success of the air war. They provided an air defense shield around the entire battle area by keeping fights deployed around the circle from southern Tainan, Clark, Da Nang, Biên Hòa, Udorn and Bangkok, while giving excellent protection to the B-52 ‘Arc Light’ missions. We will never know what attacks on our forces and bases were deterred by their presence.’

Convair’s F-102 Delta Dagger became embroiled in the Vietnam War following reports of low-flying, unidentified aircraft over the central highland region on the night of March 19-20, 1962.

Gravely concerned over the threat the unknown aircraft posed, South Vietnam’s President Ngô fình Dim asked the US government for help, and an order was immediately sent to get four F-102s from the 509th FIS at Clark Air Base over to Tan Son Nhut. The Delta Daggers took up station, but all traces of enemy air activity ceased. After flying 21 sorties, the unit was stood down. Thus began the long saga of the F-102’s presence in South-east Asia, which lasted close to eight years.

Gulf of Tonkin

Following the attacks on US warships in the Gulf of Tonkin in August 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered the F-102 to be brought in. The type would have permanent bases in Bangkok, Tan Son Nhut and Da Nang, Vietnam, and the 509th had the distinction of being the first full squadron to deploy to Vietnam. A few days later, the 405th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW), the 509th’s parent, sent its two Martin B-57 squadrons to South-east Asia.

The 509th had a detachment in Bangkok prior to August 1964. It had participated in Operation ‘Belltone’, providing interception and air defense training to the Royal Thai Air Force and its North American F-86 Sabre pilots. But with the position in Vietnam worsening, the training of Thai forces became a secondary project and the 509th went on full alert for war.

The Da Nang, Bangkok and Tan Son Nhut deployments each required six aircraft and crews to be on alert 24 hours a day. By late September, the 509th had 22 pilots deployed to Southeast Asia. This put a strain on those left at Clark, leaving only 16 pilots to handle the usual alert and training duties. The average working week for pilots was about 128 hours, which included 93 hours on alert. Time off was non-existent during the final four months of the year.

Because of the large number of aircraft and crews deployed, it became increasingly difficult to rotate the F-102s back to Clark on a bi-weekly basis, as had been done during Operation ‘Belltone’. Lt Col J. B. Burdick, chief of maintenance for the 405th TFW, came up with a workable plan for maintaining combat-ready F-102s in South-east Asia.

Highly skilled maintenance teams were assembled at Clark approximately every 15 days and dispatched to the three forward areas to ensure that all F-102s were combat-ready. This made it unnecessary to rotate the birds back to Clark every two weeks. These teams also included quality control and field maintenance specialists who brought along all the necessary supplies and equipment, so there was no delay when certain items were needed to complete the job.

Training for war

Capt Bill McDonald, a high-timer in the F-102, recalls those early days at Tan Son Nhut. ‘After a slow start, the training missions intensified. [These were] night, low-altitude, slow-moving target interception sorties and most of these missions were against [DHC] L-20 Beavers. The North Vietnamese were flying low-and-slow night-time replenishment missions and we had to get on the same level as their airplanes were flying. These missions were considered hazardous due to the extreme speed difference between the target and the fighter, compounded by very short-range contacts caused by ground return interference.

‘Several modifications were made locally to the radar at this time to aid us in low-altitude target acquisition. These changes were later adopted across the entire F-102 fleet. Scuttlebutt around the squadron had it that we were training to shoot down North Vietnamese An-2 ‘Colt’ supply airplanes that were known to be dropping muchneeded equipment to the enemy.’ Ordnance loads carried by the Delta Daggers in the Far East were an AIM‑26B Falcon air-to-air missile in the front bay, three AIM-4C air-to-air missiles in the rear bay and 12 2.75in rockets. This combination was used at Clark, Da Nang and Tan Son Nhut. The detachment at Bangkok, however, used a slightly different set-up with three AIM-4As in the front bay and two AIM-4C/Ds plus another AIM-4A in the rear bay. The Falcon series of missiles had a speed of Mach 4 at a range of six miles and gave the F-102 a greater capacity for knocking down anything that should come up to challenge it.

Capt Robert Mock describes some of the missions he flew during late 1964 and early 1965. ‘We were under the radar control of the GCI [ground-controlled intercept] site at Monkey Mountain, which would receive its orders from 2nd Air Division in Saigon. If there was any indication of an unknown [aircraft] over North Vietnam, we were scrambled. We were very good at getting airborne in less than three minutes, from long hours on the alert facility. ‘We would also intercept airliners that had strayed off course and, due to the climate, terrible weather [flying] was soon our specialty. Many times I flew an ILS [instrument landing system] final into Da Nang, with no breakout until almost touchdown on the runway. In the northern sector we were responsible for intercepting battle-damaged aircraft — I personally escorted back a couple of RF‑101 [Voodoos] that had been shot up with their pilots injured.’

In late 1964, there were approximately 20,000 US troops in Vietnam. By mid- 1965, there were about 200,000 inside the country, and that number was rising. The 509th’s F-102s were covering three bases operationally. Maj Harley Brandt, the deployment commander at Tan Son Nhut, and his team were particularly busy — the squadron records state the unit flew a total of 913 hours in September, giving each pilot an average of almost 25 hours’ flying time. Far north at Da Nang, only 75 sorties were flown that month as heavy daily rain and low ceilings hampered the flying schedule.

The long hours with no relief would continue for the 509th’s pilots until December 15 when new blood arrived from the States. This was the first major influx of reinforcements for the original group, which went all the way back in August 1964.

Welcome to Udorn

By early 1966, numbers of aircraft and personnel in South-east Asia had grown to the extent that all major air bases were beyond their normal capacity. The air defense responsibility and the workload of the 509th had reached a point at which it could no longer handle the task at hand.

Another detachment, at Udorn AB in Thailand, was established on April 18, and it was obvious that a further squadron was needed. High command decided that the 64th FIS, normally based at Paine Field, Washington, would bolster the 509th. This occurred during May-June. Maj William Winkeler, a fight commander in the 64th, remembers the monumental task of moving the squadron across the Pacific. ‘Our F-102s had been equipped for the navy’s ‘probe and drogue’-type in-fight refueling, so we flew them to Clark via Hamilton AFB, Hickam AFB and then on to Andersen AFB, Guam.

‘Prior to departure, we underwent intensive training in air-to-air refueling. The route took us over Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Nevada. Normally, we joined on the tanker over northern Oregon and went on from there. These were usually three to four-hour missions.

‘The refueling plumbing was attached to the outside of the F-102, resulting in an overall reduction in the aircraft’s performance. In our first leg over the Pacific, we had to keep our tanks filled to make it back to either the coast of California or Hawaii in case we ran into a problem. Someone was always on the tanker, which was shared by two aircraft.

If there was any indication of an unknown aircraft over North Vietnam, we were scrambled. We were very good at getting airborne in less than three minutes Capt Robert Mock. ‘The second leg of our trip, Hickam to Guam, was the longest. I remember logging about eight hours and most of the time we were in the clouds. On our finals into Clark, a thunderstorm cropped up to cause us some concern because it looked like a storm coming out of west Texas with a height all the way to 80,000ft.’

Clashing with MiGs

Capt Bob Donaldson flew a complete tour in South-east Asia in 1966-67. One sortie in particular sticks in his memory. ‘My wingman and I were launched from Udorn in northern Thailand to join up with two CH-46 helicopters at the Mekong River just north of Udorn. The mission was briefed to escort and protect the ‘46s’ from MiGs that would probably be in the area of Dien Bien Phu, North Vietnam. Just east of us was Sam Neua, the headquarters for the North Vietnamese forces in northern Laos. The goal of the mission was to place a TACAN [tactical air navigation] station on a flat-topped karst on Black Mountain. It would [be] a very valuable navigational aid for all of our strike forces going into and recovering from North Vietnam.

‘The rendezvous with the helicopters was accomplished as briefed and we headed into Laos at 8,000ft, which was the highest altitude attainable by the heavily loaded CH-46s. We would have to cross some mountains that were 6,600ft high. ‘We crossed over the Plain of Jars, and circled east of Ban Ban village at the junction of highways 6 and 7, all of which could produce plenty of ground fire.

About that time, we heard ‘Motor Pool’, the navy cruiser out in the Gulf of Tonkin, broadcast a MiG warning for the area north-east of Hanoi and tracking in our direction. A few moments later, ‘College Eye’, an airborne early warning aircraft close to us, also had MiGs on its scopes. They were approaching the Dien Bien Phu area at an altitude that was about 10,000ft above us.

‘We told the helos to press on with their delivery and we would head for the MiGs. We plugged in the afterburners, climbed to 20,000ft and, with the aid of vectors from ‘College Eye’, were able to pick up the MiGs about 30 miles ahead. I locked on to one of them and noted the overtake ring on the radar presentation wrapped around 800-900kt. I asked for permission to fire as it took a minimum of 16 seconds to arm our missiles; I got a ‘stand by’ reply. At that time, we did not have permission to fire on anything in Laos without clearance from a GCI site or ‘College Eye’. Distance was now down to less than 20 miles, so I broke the safety wire on the missile arming switches and depressed the trigger to begin the missile preparation. Again, I requested permission to fire and got another ‘stand by’. ‘Within a few minutes the target was moving away from us. ‘College Eye’ said the MiGs were in a left turn and descending. We continued our pursuit until we were just north of Dien Bien Phu.

I could see one of them, but our overtake had dropped off to nearly zero and there was still three to four miles separating us. At that point the airborne controller advised us to break off and return to the helicopters.’

Amazing missions

The most extraordinary role the delta-wing Dagger played was that of harassing Viet Cong (VC) ground forces by using the aircraft’s heat-seeking airto- air missiles. Maj Bill Winkeler recalls, ‘Since the F-102 was about the only aircraft equipped with the infra-red missiles, AIM-4Ds, they were tasked with picking up the heat from VC campfires in the jungle. From altitude, at night, they were locked on to the heat signal and fired. The results were never confirmed, but it must have been caused quite a stir, and you can imagine enemy troops gathered around a campfire after a long day’s trek and suddenly [there’s] an explosion in their midst.

‘The F-102s were also called upon to go after trucks, aircraft, helicopters etc, and they would fly above the Ho Chi Minh trails. They would usually fly north and south high above the trails and [get an] IR [infra-red] lock on any heat source they could pick up. These missions caused a lot of disruption among the North Vietnamese troops.’

Winkeler went on to say, ‘If any of the ‘Deuce’s’ [F-102’s] exploits could be classidied as ‘high-profile’, it would probably be their escort and protection of the ‘Arc Light’ missions flown by the B-52s. They were often fragged to fly lead for the SAC bombers when they first started to bomb north of the DMZ [demilitarized zone]. On station at 35,000ft, the F-102s could detect if they were being tracked by any ground units. When this happened, the B-52s would swing to the south and set up their bomb runs in a safer area. Most of the missions were flown over southern Laos or south of the DMZ.’

Early on, there was a slight problem between the B-52s and the F-102s when they joined up. Lt Harry Hoover explains, ‘Usually, we would take off and join with the bombers pretty close to their assigned bomb runs. There were usually three of them in trail. Suddenly, the entire formation would turn and exit the area. Later, we learned that since our fire control system emitted pulses similar to the MiG-21’s, coupled with the fact that our long-range silhouette was almost identical to the MiG-21, the bombers thought they were being attacked by enemy fighters. Needless to say, we performed no-lock join-ups after that.’ There wasn’t a sortie flown by the F-102s that had a better chance of drawing the MiGs than escorting B-52s.

Many Delta Dagger pilots were scrambled on air defense missions. One was Capt Samuel Dibrell, who flew most of his ops with the 64th FIS.

He describes one memorable sortie: ‘It was on my final day at Da Nang, August 9, 1969, when I was on backup for the five-minute alert which was scrambled at 4.30am to intercept two unknown aircraft coming down from the north. At 4.45am our back-up fight was scrambled to add assistance to the search for the two unknown aircraft. It was expected that these aircraft were North Vietnamese helicopters bringing in commanders, because I believe histories of the war will show that an insurgency just south of Da Nang began in early September 1969. There were very few times that both sets of five-minute birds were scrambled at the same time.

‘An interesting sideline to this sortie was that one of the first two scrambled F-102s had requested clearance to arm. I discovered after returning to base that he had picked up two blips on his scope — thankfully he was advised by the controllers that the blips were my fight coming in to assist.’

The F-102 force’s time in Vietnam was well spent. However, the risks were significant. Only one Dagger was lost to aerial combat, when a MiG-21 flying at 36,000ft downed a 509th FIS example on February 3, 1968. Two were lost to ground fire, one was written off in a ground collision with an RF-4, and three were destroyed on the ground by enemy sappers. Six more were lost due to engine failure while one was destroyed due to enemy fire, specifically a direct hit by a mortar round.

The most extraordinary role the delta-wing Dagger played was that of harassing Viet Cong ground forces by using the aircraft’s heat-seeking air-to-air missiles