A Mission of Deterrence

Few aircraft of the Vietnam era have been as misunderstood as the F-104C Starfighter. Often dismissed with the claim that it “never had a mission and never made a mark” in Southeast Asia (SEA), the aircraft’s record has been overshadowed by misconceptions and myth. Yet the historical evidence tells a far more compelling story—one of deterrence, discipline, and air superiority achieved not through dogfights won, but through battles avoided.

Between 1965–66 and 1966–67, F-104Cs deployed twice to Southeast Asia. Over those two tours, seven aircraft were lost to enemy ground defenses and one to an enemy fighter. No enemy aircraft were shot down by F-104s. To some, this statistic suggests ineffectiveness. In reality, it reflects something quite different: the success of a weapon system whose mere presence altered enemy behavior.

America’s Premier Daylight Interceptor

By 1964, the F-104C was the U.S. Air Force’s only primary air-superiority fighter. Operated exclusively by Tactical Air Command’s 479th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW), the Starfighter was widely regarded as the world’s foremost daylight air-to-air platform. Its pilots, drawn from the 435th, 436th, and 476th Tactical Fighter Squadrons (TFS), had honed their skills in demanding mock combat exercises, building a reputation as elite practitioners of high-speed interception.

The F-104 had already been forward-deployed multiple times during global crises to project American airpower. When the conflict in Vietnam intensified in 1965, it was natural that the Starfighter would be called upon again.

Operation Two Buck: Establishing Control

Following the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964, the U.S. began building up forces in Southeast Asia under Operation Two Buck. Initially, Pacific Air Forces (PACAF) resisted deploying the F-104, citing logistical complications and questioning whether the MiG threat warranted a dedicated air-superiority aircraft.

Events quickly changed that assessment.

As Operation Rolling Thunder began in March 1965, North Vietnamese (NVN) and Chinese (PRC) MiG activity increased sharply. On April 3 and 4, NVN MiG-17s attacked U.S. Navy and Air Force strike packages, downing two F-105s and disrupting bombing missions with alarming ease.

The message was clear: existing early warning and fighter coverage were insufficient.

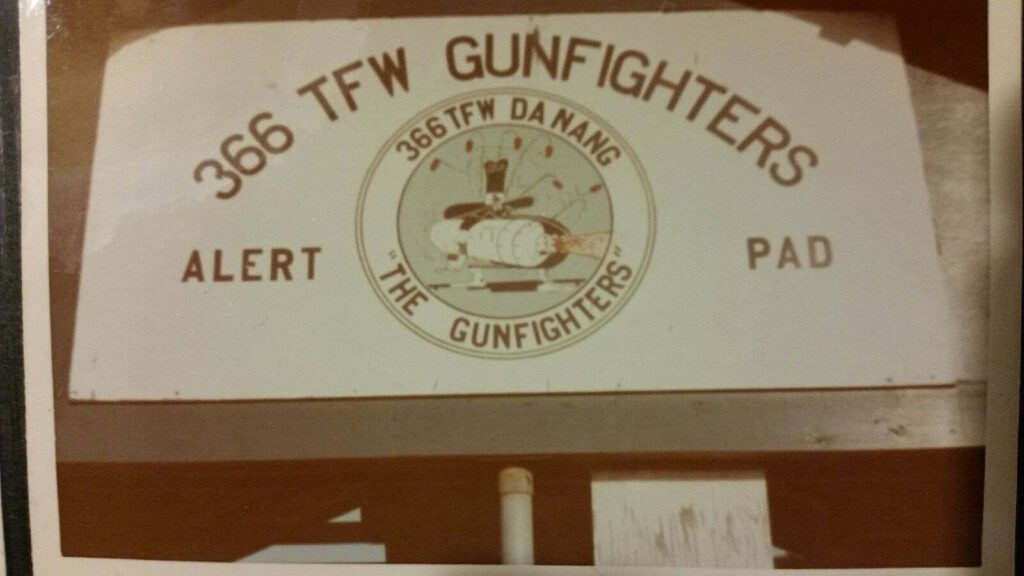

On April 7, 1965, orders were issued for F-104 deployment. The first Starfighters arrived in theater days later, operating primarily from Taiwan with rotational deployments to Da Nang. Their mission was twofold:

- Escort EC-121 airborne radar aircraft over the Gulf of Tonkin

- Provide MiG Combat Air Patrol (MiGCAP) protection for strike forces over North Vietnam

The impact was immediate. North Vietnamese MiGs avoided U.S. strike packages covered by F-104s. Chinese aircraft ceased harassment flights near the Gulf. Despite flying hundreds of sorties, Starfighter pilots encountered enemy fighters only fleetingly.

The absence of combat was not failure—it was deterrence in action.

Expanding Roles and Mounting Costs

As MiG activity declined, the F-104 began flying additional missions, including weather reconnaissance and close air support (CAS). Though not designed as a ground-attack aircraft, the Starfighter proved highly accurate with both cannon and bombs. Forward Air Controllers frequently requested F-104s for their speed and responsiveness.

But CAS work exposed the aircraft to intense anti-aircraft artillery (AAA). Losses began to mount. On September 20, 1965, Captain Philip Smith was shot down by a Chinese MiG-19 after navigational errors carried him over Hainan Island. The same day, two other F-104s collided during a night approach in poor weather.

Despite these setbacks, the 435th, 436th, and 476th squadrons collectively flew thousands of sorties while maintaining impressive mission-capable rates—often above 90 percent. Enemy MiGs continued to avoid confrontation when F-104s were present.

By late 1965, however, the F-104’s role was curtailed. The multirole F-4C Phantom II was deemed capable of performing both escort and strike missions. The Starfighter returned stateside.

Return Engagement: 1966–67

In early 1966, MiG activity increased again, now including the more advanced MiG-21. On April 29, Seventh Air Force requested the return of the F-104.

In June 1966, Starfighters redeployed—this time operating from Udorn, Thailand, alongside F-4Cs. They escorted F-105 strike aircraft and later Wild Weasel missions tasked with suppressing surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites.

On August 1, 1966, tragedy struck when two F-104s were shot down by SAMs within an hour. The loss of two experienced pilots—one-tenth of the remaining combat F-104C force—prompted reconsideration of their employment in high-risk strike escort roles.

Once again, as F-104s appeared in theater, MiG activity dropped.

Shifted increasingly into ground-attack missions in Laos and South Vietnam, the Starfighter suffered further losses to AAA and SAMs. By late 1966, upgraded with radar homing and warning (RHAW) equipment, the F-104 resumed escort duties over North Vietnam.

On January 2, 1967, F-104s participated in Operation Bolo, though not as the decoys that lured MiGs into combat. Instead, they protected the withdrawing F-4 force.

By July 19, 1967, the F-104’s Southeast Asia service ended. The aircraft was nearing phase-out from active USAF duty, and remaining assets were preserved for contingencies elsewhere.

F-104C 56-0910 was one of the first 104s to be delivered at Udorn RTAFB, 6 June 1966. It was flown by Captain James B. Trice who added a nose-art painting of the cartoon “Pussycat”

Measuring Success

During its second deployment alone, F-104 units flew over 5,300 combat sorties and more than 14,000 combat hours. Aircraft availability declined as parts shortages mounted, but the reputation of the Starfighter remained intact among those who flew with and relied upon it.

Critics often judge the F-104 by the wrong metrics. Compared to other aircraft in Vietnam, it:

- Carried smaller bomb loads

- Had limited all-weather capability

- Was less suited for sustained ground attack

But those were not its primary purpose.

The F-104C was designed for speed, climb, and daylight air superiority. In Southeast Asia, it demonstrated that air superiority is sometimes best measured not by kills recorded, but by enemy actions deterred.

North Vietnamese and Chinese MiGs consistently avoided engagement when F-104s were on station. Strike packages flew with greater confidence under Starfighter escort. Airborne radar aircraft operated without harassment.

The F-104 did have a mission in Southeast Asia: air superiority.

And in that mission, it succeeded—brilliantly.